Rotorua District, and specifically the Lakes City Council, has hosted many distinguished visitors from China over the years. Each has brought unique, history-laden, meaningful gifts to our already well-endowed city. A selection of these is on display in the Council’s Galleria to be enjoyed by the general public.

The Galleria itself has a story to tell. As is the custom from colonial days with buildings of this type, the imposing Council Chambers are reached via a long, wide parquet-floored passageway, with meeting rooms flanking both sides. The walls were dark, and covered with paintings and photographs of mayors and dignatories of by-gone days. As a result of our present Mayor Stevie Chadwick’s vision, with the support of the Chief Executive but with considerable opposition from traditionally-minded Councillors, the tokens of esteem have gone, the walls are white, the space feels airy and light, and this is now the 4th exhibition to be held here, curated by Community Arts Office Marc Spijkerbosch.

Whilst visiting the exhibitions is restricted to Council business hours, entry is free, and many people can be seen taking advantage of viewing the exhibitions – just as I was embarking on recording the images for this article, a group of Korean visitors called in.

People I’ve shown through are amazed by many aspects: the sheer number of gifts (this is a selection of more than 200 of such symbols of goodwill); the quality of the works – these are no cast-offs or seconds ! The accessibility of the meanings conveyed; and perhaps commented on most frequently, the rich variety.

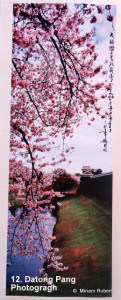

Starting with perhaps the most familiar medium for New Zealand viewers, is the lone photograph (photo 012), by Datong Pang, of Shenzhen, one of China’s leading photographers, who visited Rotorua in June 2014. About one hundred people attended the opening of an exhibition of photographs at the Aotea Centre, on June 8, 2014. There were more than 70 photographs on display by Datong Pang.

Rotorua in June 2014. About one hundred people attended the opening of an exhibition of photographs at the Aotea Centre, on June 8, 2014. There were more than 70 photographs on display by Datong Pang.

Another single representative of a familiar medium, oil painting, is

Memory of Beautiful Lake Rotorua, an Oil painting by Zhao Qingguo, a distinguished professor at Zhongyuan University of Technology, Dean of China Central Academy of Painting, Deputy of Calligraphy at the Great Wall of China General Research Institute of Painting and a renowned national artist.

Memory of Beautiful Lake Rotorua, an Oil painting by Zhao Qingguo, a distinguished professor at Zhongyuan University of Technology, Dean of China Central Academy of Painting, Deputy of Calligraphy at the Great Wall of China General Research Institute of Painting and a renowned national artist.

Mr Zhao created this 5 meter oil painting during a cultural exchange in Rotorua where he was inspired by the beauty of the region. The painting was presented to former Rotorua Mayor Kevin Winters at a ceremony that was held at the Rotorua Museum in 2013.

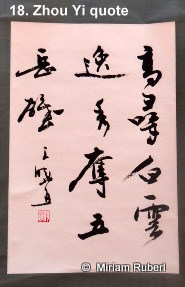

The possibly most readily recognized of Chinese arts, Calligraphy, has more examples in the

collection, with a breath-takingly wide variety of formats and themes. Starting with a scroll of ink on paper of two quotes, a popular Chinese format, the top quote is from the ancient book, Zhou Yi.

“The movement of heaven is full of power.

Thus the superior man makes himself strong and untiring.

The earth’s condition is receptive devotion.

Thus the superior man who has breadth of character carries the outer world.”

The lower phrase, also an example of Chengyu or set phrases are a type of traditional Chinese idiomatic expressions, most of which consist of four characters. Chengyu were widely used in Classical Chinese and are still common in vernacular Chinese writing and in the spoken language today. According to the most stringent definition, there are about 5,000 chengyu in the Chinese language, though some dictionaries list over 20,000. They are often referred to as Chinese idioms or four-character idioms.

“God rewards those who work hard.”

Sounds familiar, doesn’t it ?

A second scroll of Calligraphy, ink on paper bears two quotes meaning:

“There are many Chinese paintings of the beautiful rivers and mountains of China. The land is full of beauty, where artists take inspiration from the great scenery.”

Completely different, and so exciting to encounter, is a complete The Art of War by Sun Tzu, on a Scroll with 12 carat gold medium, top of photo.

Art of War by Sun Tzu, on a Scroll with 12 carat gold medium, top of photo.

As many readers will know, Sun Tzu was a high-ranking military general, strategist, tactician and philosopher who lived in the Spring and Autumn period of ancient China. Regarded as the most important and most famous military treatise in Asia for the last two thousand years, it has had an influence on both Eastern and Western military thinking, business tactics, legal strategy and beyond.The text is composed of 13 chapters, each of which is devoted to one aspect of warfare.

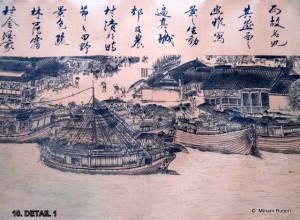

Displayed directly beneath and considered to be the most renowned work among all Chinese

Displayed directly beneath and considered to be the most renowned work among all Chinese

paintings, (it has been called China’s Mona Lisa), is a reproduction of the action-packed painting by the Song dynasty artist Zhang Zeduan (1085–1145), Along the River During the Qingming Festival. This painting captures the daily life of people and the landscape of the capital, Bianjing, today’s Kaifeng, from the Northern Song period. The theme is often said to celebrate the festive spirit and worldly commotion at the Qingming Festival, rather than the holiday’s ceremonial aspects, such as tomb sweeping and prayers. Successive scenes reveal the lifestyle of all levels of the society from rich to poor as well as different economic activities in rural areas and the city, and offer glimpses of period clothing and architecture.

Successive scenes reveal the lifestyle of all levels of the society from rich to poor as well as different economic activities in rural areas and the city, and offer glimpses of period clothing and architecture.

The scroll is 25.5 centimetres (10.0 inches) in height and 5.25 meters (5.74 yards) long. In its length there are 814 humans, 28 boats, 60 animals, 30 buildings, 20 vehicles, 8 sedan chairs, and 170 trees. The countryside and the densely populated city are the two main sections in the picture, with the river meandering through the entire length.

The right section is the rural area of the city. There are crop fields and unhurried rural folk—predominately farmers, goatherds, and pig herders—in bucolic scenery. A country path broadens into a road and joins with the city road.

The left half is the urban area, which eventually leads into the city proper with the gates. Many economic activities, such as people loading cargoes onto the boat, shops, and even a tax office, can be seen in this area. People from all walks of life are depicted: peddlers, jugglers, actors, paupers begging, monks asking for alms, fortune tellers and seers, doctors, innkeepers, teachers, millers, metalworkers, carpenters, masons, and official scholars from all ranks.

Outside the city proper (separated by the gate to the left), there are businesses of all kinds, selling wine, grain, second hand goods, cookware, bows and arrows, lanterns, musical instruments, gold and silver, ornaments, dyed fabrics, paintings, medicine, needles, and artifacts, as well as many restaurants.

Where the great bridge crosses the river is the center and main focus of the scroll. A great commotion animates the people on the bridge. A boat approaches at an awkward angle with its mast not completely lowered, threatening to crash into the bridge. The crowds on the bridge and along the riverside are shouting and gesturing toward the boat. Someone near the apex of the bridge lowers a rope to the outstretched arms of the crew below.

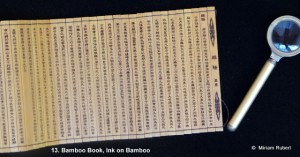

And then we have the totally surprising, diminutive ink on Bamboo book. Bamboo and wooden slips were one of the main media for literacy in early China. The long, narrow strips of wood or bamboo typically carry a single column of brush-written text each, with space for several tens of Chinese characters. For longer texts, many slips may be bound together in sequence with thread. Each strip of wood or bamboo is said to be as long as a chopstick and as wide as two.

The earliest surviving examples of wood or bamboo slips date from the 5th century BC during the Warring States period. However, references in earlier texts surviving on other media make it clear that some precursor of these Warring States period bamboo slips was in use as early as the late Shang period (from about 1250 BC). Bamboo or wooden strips were the standard writing material during the Han dynasty and excavated examples have been found in abundance. Subsequently, paper began to displace bamboo and wooden strips from mainstream uses, and by the 4th century AD bamboo had been largely abandoned as a medium for writing in China.

The custom of interring books made of the durable bamboo strips in royal tombs has preserved many works in their original form through the centuries. An important early find was the Jizhong discovery in 279 AD of a tomb of a king of Wei, though the original recovered strips have since disappeared. Several caches of great importance have been found in recent years.

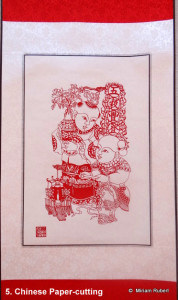

Stepping away from calligraphy, we find the immaculate example of Chinese paper-cutting in the collection. Seen up as close as one can get, there is not a single wrinkle, fold, mis-cut, wavering line!!

collection. Seen up as close as one can get, there is not a single wrinkle, fold, mis-cut, wavering line!!

Paper-cutting originated from ancient activities of worshipping ancestors and gods, and is a traditional Chinese cultural practice. According to archaeological records, it originated from the 6th century. However people believed that its history could be traced to as early as 3 BC, long before paper as we know it was invented. At that time, people used thin materials, like leaves, silver foil, silk and even leather, to carve hollowed patterns for beauty. Later, when paper was invented, people realized that this material was easy to cut, store and discard. Thus paper became the major material for them to use, and people habitually called this artistry paper-cutting, or Jianzhi in Chinese. During the Ming and Qing Dynasties (around 1368 – 1912), this artistry witnessed its most prosperous period.

Today, paper-cuttings are chiefly decorative. They ornament walls, windows, doors, columns, mirrors, lamps and lanterns in homes and are also used on presents or are given as gifts themselves. Entrances decorated with paper cut outs are supposed to bring good luck. Chinese people love to hang paper-cutting of the two characters at their doors. “福” is usually used during the Chinese New Year’s Festival, indicating people’s wishes for a lucky year. “囍” can often be seen at the windows or door of newly-weds, indicating the happiness of a wedding. Red paper is the colour of choice – it brings good luck! In this example, the red paper is laid UNDER the cut white paper. A must-see for scrapbook aficionados and admirers of Matisse !!

Leaving the walls momentarily leads us on to the display cases, and a collection of ancient, in New Zealand terms, coins dating back to 118 BC, and modern (20th century) stamps of Chinese leaders, and a single example of a Hand Fan, made of hand carved sandalwood and ivory. Like the brush pen or chopsticks, Chinese hand fans are also an important symbol of China, and one that has played an important cultural role since ancient times. When exactly the Chinese invented hand fans is not recorded. But we do know that it was rather a discovery of the fanning function. It all started when a farmer was irritated by lots of flies and mosquitoes, he was so frustrated that he picked a big leaf with a long stem from a plant close by to drive the pests away. To his delight, his effort resulted in cooling air movements. Hence, the hand fan was invented.

Fans became very popular in during 202 B.C.-204 A.D. in the Han Dynasty. Their handles were made out of bamboo from the Central China’s Hunan Province, while the best fan has a surface of white silk from East China’s Shan-Dong Province. Fans of aristocrats and scholars became more a decorative tool and a symbol for them rather than for the purpose of keeping them cool. They would also often wave their fans to show off their grace when composing or thinking about poetry. When fans were not used, they were concealed inside the sleeves or hung from the waist. Today, modern oriental hand fans come in all kind of styles and material, with the sandalwood fan being the most popular. Ladies who hold it gracefully in their hand are seen to display elegance and femininity, conveyed by it’s outstanding characteristics and distinct scent coming for the wood. This subtle fragrance gives the holder an enchanting and refreshing feeling which no expensive perfume is thought to be able to offer. Hand fans today are rarely used for fashion purposes throughout China, but ladies still carry them in their handbag for cooling purposes in summer and also for performances of the traditional hand fan dance.

Another display case contains a Bianzhong an ancient Chinese musical instrument consisting of a set of bronze bells, played melodically. These sets of chime bells were used as polyphonic musical instruments and some have been dated at between 2,000 to 3,600 years old. They were hung in a wooden frame and struck with a mallet. Along with the stone chimes called bianqing, they were an important instrument in China’s ritual and court music going back to ancient times.

A favourite with many is the Qilin figurine. The qilin is a mythical hooved chimerical creature said to appear with the imminent arrival or passing of a sage or illustrious ruler. It is a good omen thought to occasion prosperity or serenity. It is often depicted with what looks like fire all over its body. This bronze example has ‘greened’ beautifully, showing off its ornamental markings to great effect.

Alongside the Qilin is a cooking receptacle that would make many a New Zealand cook wonder at the modest portions it implies ! Referred to as a “Ding“, it is an ancient cooking vessel with two loop handles and three or four legs, a symbol of power.

“And what about pottery?” you might well be asking by now … for you this exhibition has a Porcelain vase / urn The crackles, or “crazing“, are caused when the glaze cools and contracts faster than the body, thus having to stretch and ultimately to split.

The art historian James Watt comments that the Song dynasty was the first period that viewed crazing as a merit rather than a defect. Moreover, as time went on, the bodies got thinner and thinner, while glazes got thicker, until by the end of the Southern Song the ‘green-glaze’ was thicker than the body, making it extremely ‘fleshy’ rather than ‘bony.’

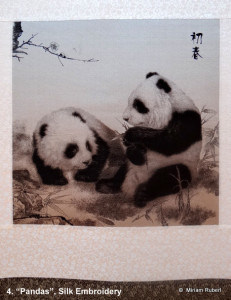

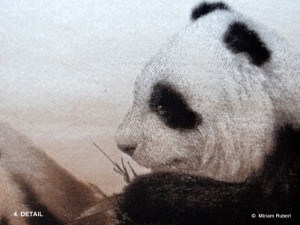

Which brings me to the last, perhaps most intriguing category of gifted items, silk embroidery and brocade. Chinese embroidery has a long history since the Neolithic age. Because of the quality of silk fibre, most Chinese fine embroideries are made in silk. Some ancient vestiges of silk production have been found in various Neolithic sites dating back 5,000-6,000 years in China. Currently the earliest real sample of silk embroidery discovered in China is from a tomb in Mashan in Hubei province identified with the Zhanguo period (5th-3rd centuries BC). After the opening of Silk Route in the Han Dynasty, silk production and trade flourished. In the 14th century, Chinese silk embroidery production reached its high peak. Today most handwork has been replaced by machinery, but some very sophisticated production is still hand-made. Modern Chinese silk embroidery still prevails in southern China.

The work that is by far the hardest to comprehend that it is actually worked in embroidered silk on silk is Pandas, The giant panda lives in a few mountain ranges in central China. As a result of farming, deforestation, and other development, the giant panda has been driven out of the lowland areas where it once lived. The giant panda is a conservation reliant endangered species.] A 2007 report shows 239 pandas living in captivity inside China and another 27 outside the country. Wild population estimates vary between 1500 to 3,000. While the dragon has often served as China’s national emblem, internationally the giant panda appears at least as commonly. As such, it is becoming widely used within China in international contexts, for example as one of the five Fuwa mascots of the Beijing Olympics.

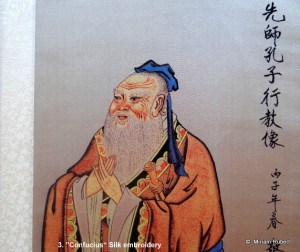

Just as exquisite, yet more clearly visible as stitched, is the scroll presentation of Confucius (551–479 BC), a Chinese teacher, editor, politician, and philosopher of the Spring and Autumn period of Chinese history. The philosophy of Confucius emphasized personal and governmental morality, correctness of social relationships, justice and sincerity. Confucius’s principles had a basis in common Chinese tradition and belief. He championed strong family loyalty, ancestor worship, respect of elders by their children and of husbands by their wives. He also recommended family as a basis for ideal government. He espoused the well-known principle “Do not do to others what you do not want done to yourself.”

Just as exquisite, yet more clearly visible as stitched, is the scroll presentation of Confucius (551–479 BC), a Chinese teacher, editor, politician, and philosopher of the Spring and Autumn period of Chinese history. The philosophy of Confucius emphasized personal and governmental morality, correctness of social relationships, justice and sincerity. Confucius’s principles had a basis in common Chinese tradition and belief. He championed strong family loyalty, ancestor worship, respect of elders by their children and of husbands by their wives. He also recommended family as a basis for ideal government. He espoused the well-known principle “Do not do to others what you do not want done to yourself.”

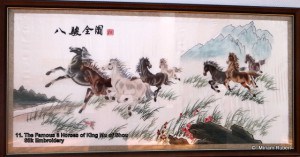

The famous 8 horses of King Mu of Zhou, Embroidered silk mounted and framed, again requires close examination to detect that it is actually not painted. Horses are a traditional Chinese art subject because they have very positive symbolism in China, and in Feng Shui. It has the meaning of horses bringing success.

close examination to detect that it is actually not painted. Horses are a traditional Chinese art subject because they have very positive symbolism in China, and in Feng Shui. It has the meaning of horses bringing success.

In China horses are a symbol of power, endurance, beauty freedom and passion. It has the special meaning of success in your career “Horses Come and Bring Success” is the saying on many of them. The recommendation is to display the galloping horses high up coming into your home, important rooms or office. Putting these horses in the southern sector of your living room or family area brings rising success to you and your family.

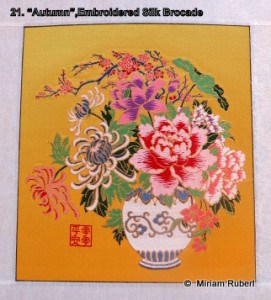

Lastly, two of the several embroidered silk scrolls depicting birds and flowers. Stand-outs for me were these two : Pheasant on top of flower The bird is called Chinese copper pheasant or Golden Pheasant. There is a four word Chinese Phase for “the bird on top of the flowers” – which means you may improve something which is already good – the “icing on the cake.” And examples of the Embroidered Silk Brocades, a class of richly decorative shuttle-woven fabrics, often made in coloured silks and with gold and silver threads. Dating back to the Middle Ages, brocade fabric was one of the few luxury fabrics worn by nobility throughout China.

Lastly, two of the several embroidered silk scrolls depicting birds and flowers. Stand-outs for me were these two : Pheasant on top of flower The bird is called Chinese copper pheasant or Golden Pheasant. There is a four word Chinese Phase for “the bird on top of the flowers” – which means you may improve something which is already good – the “icing on the cake.” And examples of the Embroidered Silk Brocades, a class of richly decorative shuttle-woven fabrics, often made in coloured silks and with gold and silver threads. Dating back to the Middle Ages, brocade fabric was one of the few luxury fabrics worn by nobility throughout China.

From the 4th to the 6th centuries, the production of silk was seemingly non-existent, as linen and wool were the predominant fabrics. During this period, there was no public knowledge of silk fabric production except for that which was kept secret by the Chinese. Over the years, knowledge of silk production became known among other cultures and spread westward. One of the sets of these brocades generally depicts the four seasons – represented by the flowers, shown here is Autumn.

All in all, a very filling and satisfying experience ! I invite you to come and share in the feast.

Miriam Ruberl, Rotorua Correspondent, November 2015

Miriam Ruberl is a mixed media, experimental artist currently living in Rotorua. She likes working with every day materials such as locally harvested red ochre, calico, waxes of various sorts, combining them in ways that surprise and remind people of days gone by. Her focus is on making increasingly authentic, personally generated nature-inspired art, to the neglect of illustrative, representational and derivative or “second-hand” art.

Miriam Ruberl is a mixed media, experimental artist currently living in Rotorua. She likes working with every day materials such as locally harvested red ochre, calico, waxes of various sorts, combining them in ways that surprise and remind people of days gone by. Her focus is on making increasingly authentic, personally generated nature-inspired art, to the neglect of illustrative, representational and derivative or “second-hand” art.

Miriam has exhibited extensively throughout the North Island, leads workshops from time to time, and is active in a variety of local activities. The red ochre series Kokowai / Takau : Seeds of Creation can be seen in the Lakes Council Chamber Galleria along with 4 other artists until end September. This space, while public, is neither your usual type of gallery nor a temporary space, and lends itself to her philosophy that modern-day artists can back and support their own efforts without relying purely on commercial or vanity galleries to get seen.

“There are a number of immensely talented, independent, full time artists in various mediums in the area, which provides me with a rich social and artistic life, as well as the inspirational environment of forests, lakes, and geothermal activity”, says Miriam.

http://artshow.co.nz/gallery/Miriam+Ruberl http://miriamruberl.weebly.com